By Michelle Fish

It’s about a one mile walk from Martha Vasquez’s house to the parcel of land she farms with the help of her husband, Francisco. I say walk, but what I really mean is climb. The narrow path up is steep, and very slippery. So steep that I had to take more than a couple of rests along the way to make it to the top. And, for a moment, I doubted whether I’d get there.

This is the walk she makes at least two times a day: after she gets her children ready for school, and then again, to prepare lunch for the family. She told me that if she’s really in a hurry, she can do it in 12 minutes. She’s tough, and she’s fearless. But she’d have to be to have achieved all that she has.

Martha Vazquez Sanchez in her coffee field, next to her hand pulper for taking the fruit off the cherry.

The Village

She lives in a remote, tightly-knit community known as Esperanza Morrison in the Tumbala region of Chiapas. It was once a large coffee plantation owned by a German immigrant. When he died, he left the land to his workers, primarily of Mayan descent, part of the Ch’ol tribe. They have their own language and distinct customs. Very little Spanish is spoken by anyone over 30.

Martha’s adoptive parents were among the recipients of the land. And she inherited it from them when they passed away.

Coffee is the community’s primary economic opportunity. But it has not been a road paved in gold for her town. The small parcels that make up their production are far from the infrastructure needed to get their crop to market. For most of the years that Martha has been a coffee producer, she has been forced to rely on the sub-par prices paid by the Cayotes, middle-men who show up in a pick up truck during harvest to pay cash for the day’s crop. Often what they pay is below even the already low C-Market price. It may also be below what it cost the producer to grow the coffee in the first place. But the farmers need the cash to feed their families, and nobody else is showing up to buy.

Kids on the corner in Esperanza Morrison.

Finding a New Way

Martha knew that there had to be a better way. She heard about Maria Esther and Pascual Castillo, and the work they were doing at Finca La Fortaleza. So, she figured out how to get herself to the town of Chilon, about a four hour drive away, with a sample of her coffee. She parked herself in Pascual’s office and waited, refusing to leave before she could see him. Eventually, she got her chance. She told him that her community grew the best coffee in the world, and that he would want to buy it once he had tasted it.

It’s a line he’s heard many times before. He and Maria Esther are already working with about 2,000 small producers in the region. But there was something about her intensity and her confidence that intrigued him. So, he roasted up her sample and gave it a try.

It didn’t go quite the way she planned.

Although he could taste the potential in the sample, he could also taste the defects caused by the way the coffee was picked and processed. He could taste that not all of the beans were picked at their peak moment of ripeness. And he knew that the moldy overtones came from the way the coffee was dried in the open air. As a method of drying coffee, it works great until it doesn’t. If you don’t get the coffee covered up before the rain, the excess moisture seeps in and spoils the beans. Although open air drying is common in much of the coffee producing world, Chiapas is in a particularly wet environment, making it even more of a challenge.

But he decided to make a deal with her, anyway. He would send one of Finca La Fortaleza’s advisors to her community to provide technical expertise to improve her agronomy and her processing techniques. And, if she took the necessary steps to improve the quality of her coffee, he would buy it.

Solar Drying Beds

Her first task, he told her, was to build a solar drying bed that would keep her coffee safe from the rain. So, she went home and sent her husband out into the forest to get the wood to build the frame. And she showed her neighbors how to do it, too.

That one change, by the way, improved more than just the coffee. Martha told me that before they had the beds, they were constantly thinking about when the rain might come. They would often have to stop in the middle of whatever else they were doing to scramble to cover the coffee. Now, they don’t have to worry.

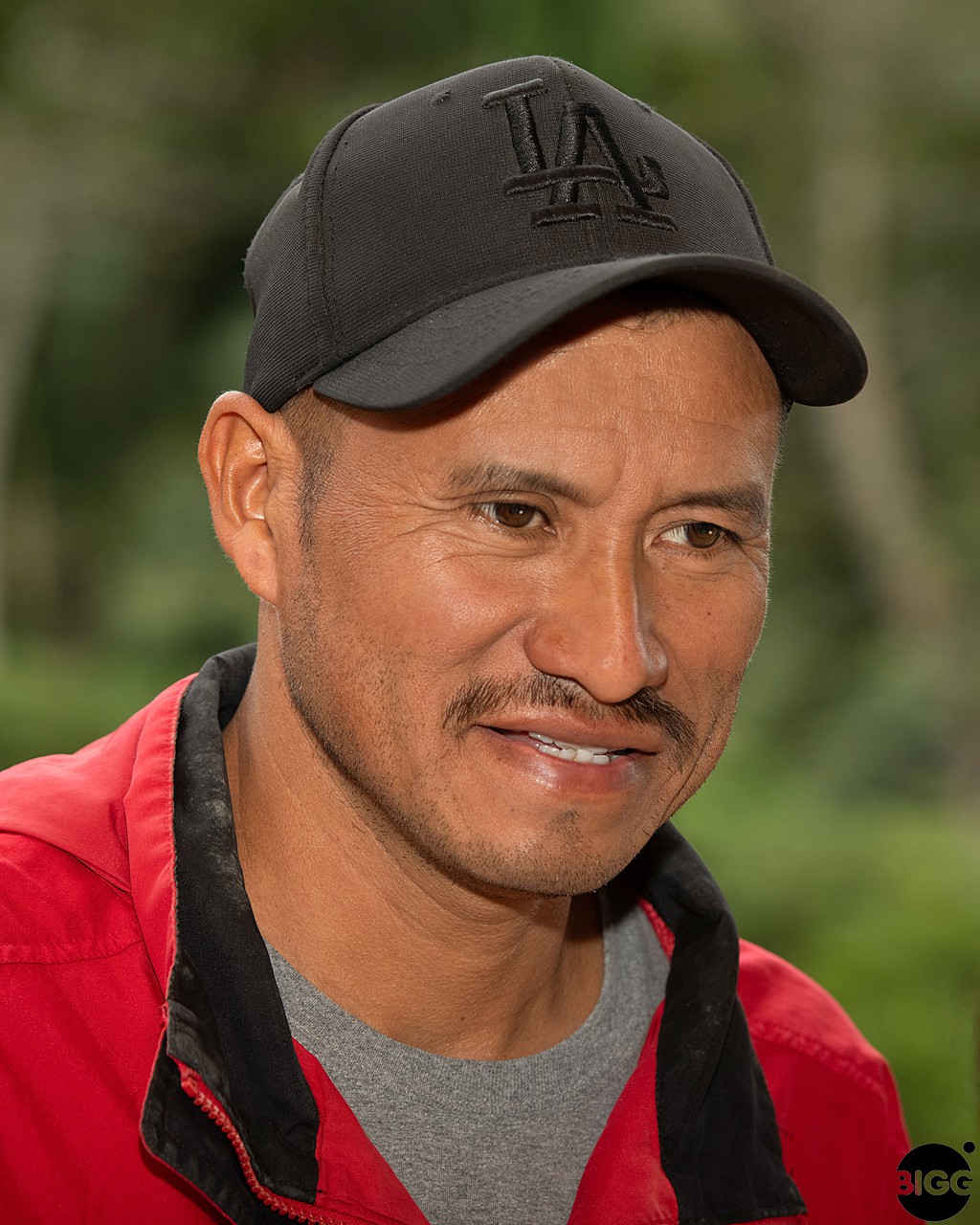

Touring Martha’s first solar drying bed with Pascual Castillo (center).

Beginning Our Partnership

In the year that she has been implementing and sharing the technical advice she received from Pascual and Maria Esther, the quality of her community’s coffee has improved dramatically. So, when it came time for them to select the four small producers that would be a part of our Farm-Direct partnership, they decided to include Martha.

She is the face, and the lead producer for a group of 30 of her neighbors, mostly male, and many significantly older than she is. In a culture in which women are typically constrained to traditional roles, Martha is unequivocally in charge. She is the quality control person, making sure that her neighbors follow the proper practices. And she handles the money, doing the disbursements based on everyone’s individual production.

In her community, there are approximately 200 small producers. Selecting the initial 30 that would be included in the Partnership was a challenging decision. In part, it was based on which of them were doing the best job implementing the improved growing and processing techniques. Not everyone is open to growth and change, particularly when the promise of a better price is one that has, in their experience, never come to fruition, regardless of what they do. Investing in the promise of something better just risks too much heartbreak when it doesn’t pan out.

But, as in so many of the remote, primarily indigenous villages in Chiapas, there was another layer of complication.

Martha leading the meeting between Pascual, Maria Esther, Bob and I, and Kathya Irias, and the 200 small producers in her community.

Coming Out of the Shadows

Most of the people there weren’t born in city hospitals, so they don’t have official birth certificates. They don’t have the equivalent of a social security number or a tax id. In fact, most have never paid taxes. And have never received government benefits. They are unlikely to have a bank account or a cell phone. Many of them don’t even speak any Spanish. They are in so many ways, but especially on paper, invisible. Their invisibility is a large part of what keeps them in a multi-generational prison of poverty.

This doesn’t matter to Cayotes, who operate under the radar themselves. And who, in fact, can exploit the invisibility of the producer to leverage even lower prices. After all, who are they going to complain about it to, when nobody “official” acknowledges that they exist?

But it does matter to Maria Esther and Pascual. Their coffee processing company COFINCAF operates fully in the light, with complete traceability to each of the producers that they work with. So, in order to be a part of the Partnership, the individual producers would need to wade neck deep into the heavily bureaucratic and bewildering process of becoming “official.”

It requires gathering as many bits of identifying information as they can. Then transportation, and accommodations for two nights away as they undertake the 10 hour journey to get to a government office. And then someone to translate for them from Ch’ol to Spanish, and back again. Plus, money for the fees and paperwork. For most of the members of Martha’s community, these obstacles are too burdensome to overcome on their own. So, Maria Esther made it her personal project. As of now, 30 of the small producers are “official.”

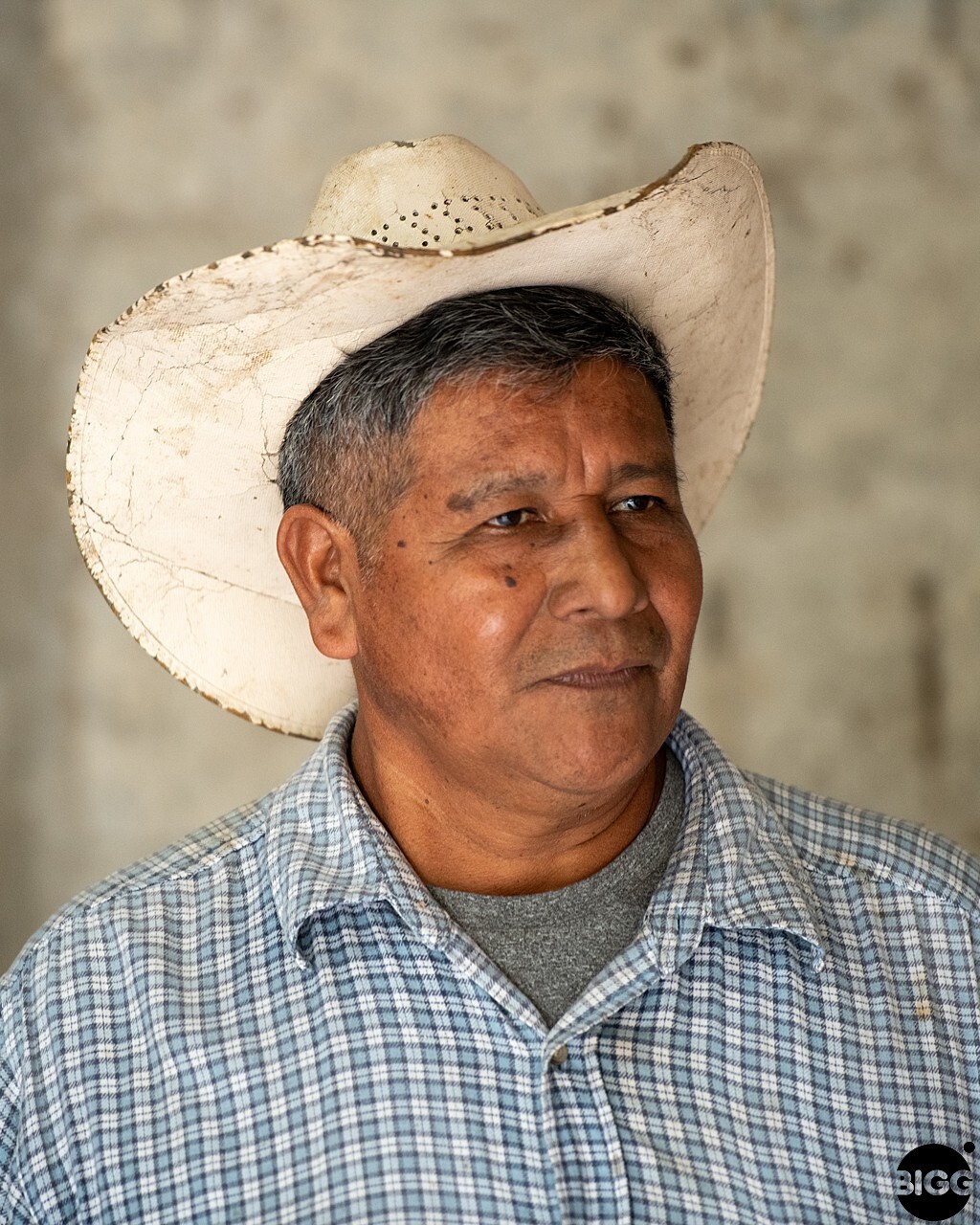

From L-R: Bob and Michelle Fish, Martha & Francisco Vazquez and Maria Esther Saut. Back row: Pascual Castillo

The Future

As our Partnership grows, we will need more of Martha’s community’s coffee. The hope is that those that haven’t engaged with the improved agronomy will see Martha’s mighty band of 30 receiving the benefits of a better price and a guaranteed market. And it will inspire them to change.

In fact, our last visit there started with Martha leading a community meeting of all 200 producers. They were there to ask us how they can all be included. And, of course, there will be much work to do for Maria Esther as she helps them achieve their status as citizens, one at a time.

Martha prepared a beautiful lunch for our group after our walk on her land.

On the Mountain

But back to that steep climb up the mountain that I wasn’t sure I could do.

Martha is justifiably proud of her land and her coffee. The setting is gob-smackingly beautiful, a lush tropical forest with sounds of birds and water in the distance. And her plants are healthy and thriving. She took obvious delight in showing us around, telling us about her plans for new plantings and better pruning.

She and her husband Francisco have three children: 13 year old Emmanuel who is in secondary school, a five year old son Hezron Gael, and a four year old daughter Sonia Lucero. While we were walking her land, I asked her what her dreams were for her children. It’s the one time she hitched a little, when she told me that her dreams are for all of the children of her community.

Martha with her son Hezron Gael (left), and her daughter, Sonia Lucero (in the pink.)She would have liked to have pursued an advanced education, but it wasn’t economically available to her as a child. She wants to change the fortunes of her town, so that every child has the right and the ability to have a dream that they can follow for themselves. That’s what drives her, and that’s why she works so hard. And that’s why we are so honored to be her partner on the journey.