By Bob Fish

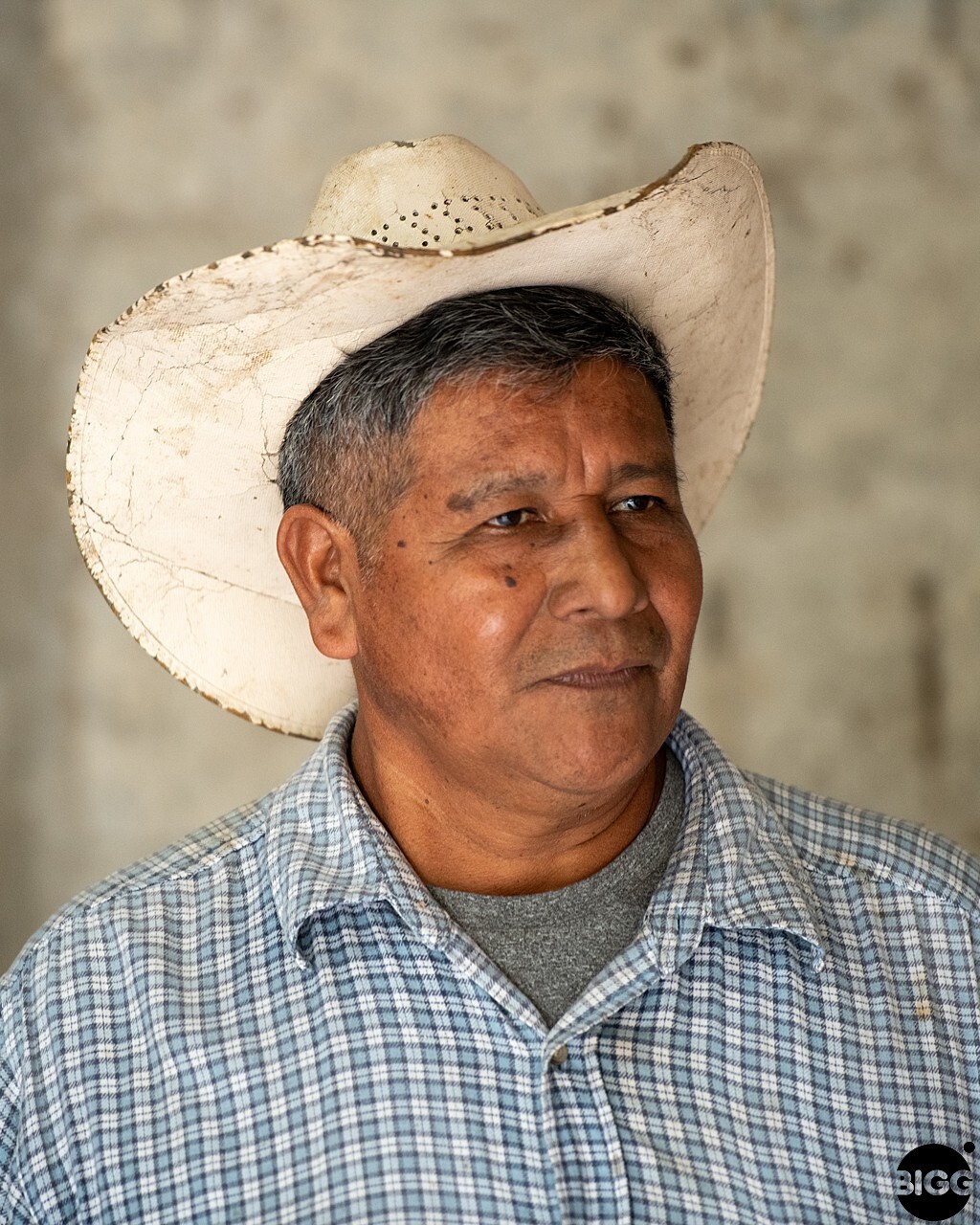

In August of 2021, I went to Chiapas, Mexico to meet with Pasqual Castillo and Maria Esther Saut, the husband and wife team at the Fortaleza Coffee Farm. Our friends and partners from Living Hope International had introduced us, and we were intrigued by the work they are doing for coffee farmers, helping them recover from a plague of Roja (rust) in 2009 that completely wiped out the coffee growing industry in that part of Mexico. Roja devastated the livelihoods of farmers and families that were already living on the margins.

Pasqual had built his decades long career in his family’s business: coffee processing and exporting. Their role is to find the best quality coffee at the lowest possible price. They export to roasters and coffee shop chains all over the world based on something called the C-Contract. It is a tool of the global marketplace that arbitrarily sets a price based on anticipated supply and demand, not the cost of production. While he was with his family’s business, Pasqual was a part of the commodities marketplace, extracting the maximum value for the middlemen and brokers, almost always at the expense of the farmer. There are many years when the C-Contract price per pound is actually less than what it costs most farmers to produce the crop. Obviously, that’s not sustainable.

From L-R: Maria Esther Saut, Pascual Castillo Saut, Bob Fish, Pascual Castillo Moctezuma, and Juan Carlos.

Coffee in Chiapas

Coffee production was once the primary economic engine of Chiapas. Over the decades, Pasqual got to know many growers, big and small. He witnessed their struggles to stay afloat and saw their fierce dedication to their land and their families. And he watched as more and more small farmers gave up growing coffee altogether. Unable to make a living, they turned their lands over to other uses. Gradually, he became convinced that the system itself was broken, and would inevitably lead to the collapse of coffee as a crop.

The Roja epidemic of 2009 was the catalyst for Pasqual and Maria Esther to change everything. They believed strongly that coffee could make a comeback in Chiapas. With education on better farming techniques, access to rust resistant coffee varietals, and hands on coaching and encouragement, the small growers of Chiapas could reestablish coffee as an economic driver in the region, providing opportunities for families to thrive. So, they turned their lives upside down to become the change they wanted to see in the world.

La Fortaleza is Born

Pasqual and Maria Esther owned a substantial cattle ranch in Chiapas on land that had once grown coffee. They began the painstaking process of rehabilitating their cattle-trodden acres so that it could support a coffee crop and become a model farm to “prove out” their new techniques. To start, they invested heavily in research on rust resistant coffee varietals and grew hundreds of thousands of them that they distributed free to regional coffee growers. They have shared their knowledge of sustainable coffee growing practices with literally hundreds of small farmers.

Rust resistant varietals growing in La Fortaleza’s seedling nursery.

At great personal expense, they invested in the machinery and equipment required to process a coffee crop, including a state-of-the-art dry mill. If there is a pinch-point for small growers, it is access to processing at a dry mill – a crucial step in the chain of coffee. Often dry mills are at a significant distance from the fields where coffee is produced. Many small growers don’t have access to transportation for their crop. That makes them vulnerable to the cayotes (small scale coffee buyers) who come along, offering to buy their coffee on the spot, always at a cut-rate price.

Maria Esther in the dry mill at La Fortaleza.

Perhaps most importantly, they invested in long-neglected people. As an example, they provided breast cancer screening in a community that doesn’t have access to basic health care. In short, they went all in. And slowly but steadily, the tide is turning in their part of Chiapas.

The Small Growers

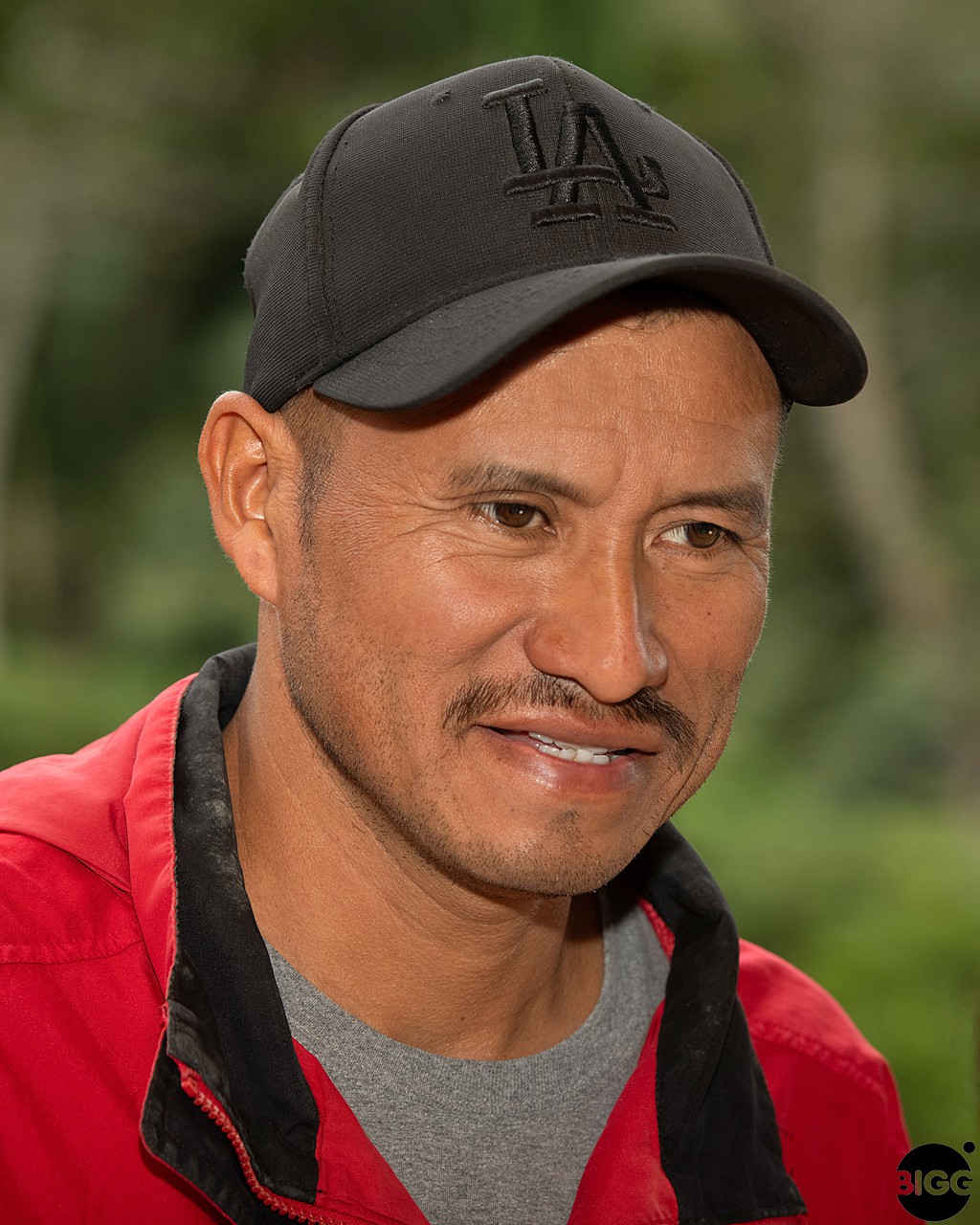

I had the opportunity to meet many of the farmers out of the hundreds they are working with. Farmers like Ishmael and his family have found a new path to success thanks to the work of Pasqual and Mary Esther. It takes three years for a coffee seedling to a produce its first commercial harvest. Using their techniques, including growing companion crops of beans and corn to shade the young coffee plants while they reach maturity, helped Ishmael to be able to feed his family as he turned his land back to producing high quality coffee.

Ishmael among the corn and bean plants that provide shade for his rust-resistant coffee seedlings.

Right Up Our Alley

Boy, this all sounds like it’s right up OBIIS’s alley, right? And in late October, Michelle and I travelled back to Chiapas with our partners: Miriam Morales and Jorge Ferrey from the El Recreo Coffee Estate in Nicaragua, Rich Schaasfma from Paramount Coffee, and Manlio Huacuja from Living Hope. We were there to be “boots on the ground,” of course, and finish the vetting of the farm that I had begun on the previous visit. But truth be told, we were already half-way to being in love with their passion for their mission, and the way it was changing lives on the ground. Michelle and I were there to do a final gut check on our alignment of values. We were there to start the process of closing a deal.

So why didn’t it work?

It’s complicated. Isn’t it always? But I think part of the answer lies in just how radical OBIIS’s reinvention of Farm-Direct really is. We aren’t looking to make the C-Contract work in a more humane way for farmers. We are looking to blow the whole thing up all together.

We want life-long farm partners, not coffee bean vendors. And, we want the price that we pay for their coffee to be based on how much it costs to produce their crop in a sustainable way, pay their people well, and invest in their communities, with some on top so they can make a profit. We don’t care what brokers and traders estimate the global flow to be, and we’re not interested in riding the vagaries of an artificial system that turns goods and people into dots on a graph.

Maria Esther and Michelle Fish deeply engaged in conversation at La Fortaleza.

Win-Win

If we uncouple coffee from the global markets, and just focus on the farmer and their needs, the rewards of that relationship are a powerful win-win for everyone in the chain. Our Farm-Direct partners have the surety of knowing that year over year, they can invest and make long term plans for their farms and their communities, and we will be there, shoulder to shoulder, on their journey. In return, BIGGBY COFFEE owner-operators have price stability and a guaranteed supply of quality coffee – a real win-win, particularly in the age of climate change.

Another very important side benefit: we will have illuminated the entire chain of coffee, from field to cup. Our Farm Partners will know us, our owner-operators, and our customers. And our owner-operators and our customers will know our farmers – a name, a face, and a place for every cup of coffee sold at a BIGGBY COFFEE.

The Power of the C-Contract Framework

For the past couple of years, the C-Contract price has been artificially low. It just so happens that this year, for the first time in about a decade, it shot up more than 200% from around $1.00 a pound to about $3.00. That’s not because the world got wise to how much it actually costs to produce a cup of coffee. Rather, there was an early frost in Brazil (the world’s largest coffee producer) followed by a drought. The supply of coffee is projected to be tighter this year, and the price went up.

But to be clear, the uptick in price has nothing to do with how much it costs a farmer in any given region to produce a crop. It’s simply a product of supply side economics. And already, the price is falling again, and is likely to continue to do so.

As much as Pasqual was a very successful processor and exporter of coffee, largely by leaning heavily on the C-Contract framework, he has become a fierce advocate for the smaller producers that he’s helping grow… but it’s still all within the context of the global market. He wants the very best for his farmers, and to that end, he wants to get as much as possible out of the buyers, particularly in a year in which the C-Contract price is artificially high.

That’s not our framework, and it’s not our playing field. Which brings me to the next point on why it didn’t work.

Basic Economics

For us, Farm-Direct is a radical rethink of the business model of coffee. Let me say that again in a different way: it’s business – ethical, conscious business – not charity. The price we pay for coffee has to work for our owner-operators. And the price they quoted us was just way too high.

Trust is the foundation of all real partnerships. We take our partners, and our potential partners, at their word when they quote a price. We ask for it to be transparent, and we will not negotiate them down. After all, we want to pay the price that meets the criteria I outlined earlier: what it costs to produce the crop in a sustainable way, pay their people well, invest in their communities, with some on top so that they can make a profit.

To get there is easier when the spot price is low. But frankly, it should have nothing to do with the spot price, which is an artificial construct of global markets, and is as likely (more likely) to crash than it is to rise. Frankly, the C-Contract is a vestige of colonialism wrapped in capitalist trappings. You can tell because the farmer almost always loses in the deal. It’s like a casino, and the C-Contract is the House. The House always wins.

A Different Sandbox

So in this case, with two entities both working to better the outcomes for the farmer, it was more complicated. Our role is outside the sandbox, but most of the industry only knows the sandbox. Change is hard. But that doesn’t mean that we are going to stop trying. Pasqual and Maria Esther are doing amazing things in Chiapas, and who knows what the future may bring. We wish them well.

And we look forward to sharing the news about our next potential Farm-Direct partnership. I’ll give you a hint… we’re headed to Ethiopia in a few weeks. Stay tuned!