By Michelle Fish

One of the cruelest oxymorons in the English Language is “Civil War.” I think we all know that there is no such thing. War, in whatever form it comes, is brutal.

I think, though, that despair and trauma might cut even deeper when the brutality comes from within your own country, within your own community. There is something especially ugly about a fight to the death between your former neighbors, friends, and maybe even your own family. And the only thing you can be sure of is that there are no winners.

Civil War is no stranger to coffee country. We don’t have a Farm-Direct partner or project whose country hasn’t been touched by it.

And this isn’t ancient history. Nicaragua and Guatemala were both embroiled in conflict in the 80s and 90s. Sierra Leone ended their Civil War in 2002. And Mozambique ended theirs in 2019, which makes their peace younger than OBIIS.

The question that has always fascinated me is what happens the day after the peace accords are signed? When the warm glow of the ceremony is over, and the ink is drying on the signature lines, how do you take the idea of peace and turn it into reality? How do you re-knit the fabric of society together again, after so much bloodshed and loss?

Bob and I were about to find out on a recent visit to Colombia.

On our way to Icononzo in November of 2025.

But First, Trying Something New

We’ve often described our work in OBIIS as building the spaceship while we fly it. That just means that we’re always iterating on how we do everything, from the language we use to describe Farm-Direct to the way we find new prospects.

One conclusion that we have come to over the last seven years is that unless we’re willing to buy a fleet of trucks (or trucks and ships, in the case of Africa and Asia) and pick up the coffee ourselves, there will almost always be some kind of middleman between us and the producer.

After all, only a very rare subset of producers has the financial resources and international connections to farm, process, transport, export, and import their own coffee. They are, almost by definition, bigger players, or people who have already achieved a high level of success before they entered coffee. Coffee farming is a hard business to be in, no matter what your size, but those folks don’t really need us.

It’s the small producers, particularly the ones in remote communities, far away from the infrastructure of the coffee industry, that are invisible to the rest of the world and choked out of real opportunity.

So, if there are going to be some middlemen in the supply chain, what if we could partner with companies that are values aligned with OBIIS, focusing on people, the planet, and improving communities?

And, rather than reinventing the wheel with every new producer partnership, what if we could work with values aligned companies that have already figured out all the links in the chain? And what if the work they do for the compensation they receive could be completely transparent to all parties? Sounds like a dream, right? Meet Caravela Coffee.

Our team with members of Caravela coffee, from Right to Left, Alejandro Cadena, CEO; Juan Carlos Esteban Garcia; and, Nicolas Herrera.

Caravela and Colombia

We have been running into their team for years at events all over the world. And while we have been deeply skeptical, in general, about middle-men and their role in coffee, the way Caravela talked about their approach was interesting.

Our impression was that they are deeply involved at origin in the communities in which they are buying coffee. They embed where they are working, bringing in agronomy assistants to help farmers learn and grow. They hire locals on the ground to help manage the process. And, they pay better than market prices for the parchment coffee they procure. They talk about real relationships with producers and communities. And they say they are committed to promoting environmentally sustainable practices among the farmers with whom they work.

Bob and I have wanted to find a producer partner in Colombia for a long time. And Caravela has been involved in communities in Colombia for a long time. So, we thought we’d try something new.

In August of 2025, we asked Caravela to introduce us to producers in two of the communities in which they operate. In OBIIS-Speak, a “first visit” is all about discovery. We want to understand what producers are up to. Does it align with our values? Is there a community vision? We’ve been to around 200 farms all over the world. And we have five partners. So, the process to become a partner is both long, and rather intrusive in terms of the questions we ask and the time we take in getting to know the players. And in the end, we don’t find a fit far more often than we do. This time, it wasn’t just the producers we were considering. We wanted to see exactly what Caravela is up to in coffee communities. The only way to know is to go Boots on the Ground.

The OBIIS team in August, 2025, debriefing at the Artisan Hotel in Bogota, Colombia

First Visit

On that first trip back in August, after we landed in Bogota, our OBIIS team split into two groups. One team went to Herrera, a subject for another story. And the other (Bob, Rich Schaasfma of Paramount Coffee, and our friend and colleague Chad Trewick) went to Icononzo. It’s a four-hour drive from Bogota to a world that is both steeped in the very bloody history of Colombia’s armed internal conflict, and was described to us a shining example of what real peace can look like. The people in both communities were very compelling. And the work that Caravela is doing was impressive.

After the visits were over, we had hours of debate about which path to follow. But there was something about what I was hearing from Bob, Rich and Chad about Icononzo that I couldn’t shake. The idea that combatants and victims could come together through coffee seemed almost too good to be true. I knew we were going back to Icononzo for a second visit.

Chad, Rich and Bob, with the Caravela team and some of the small producers in Icononzo, from their first visit in August of 2025.

A Brief History

Disclaimer: I’m no historian. And I’m sure there are plenty of people who know way more than I do that will read this and take issue with what I leave in and what I leave out. Because, in reality, it is a very complicated and nuanced story, and there are way more than two sides to the bloody conflicts that have chewed their way through Colombian society since the inception of the country.

But to really understand what is unfolding in Icononzo today, it’s helpful to have a little context.

The Spanish first arrived in what is now Colombia in 1499. They rapidly expanded their colonial empire all through central and south America right up until they were “kicked out” (in Colombia, at least) in the 1820s. After a long and violent struggle between various internal groups fighting for control (and not without a lot of interference from other major world powers, including the United States), the Republic of Columbia was established in 1886.

In the 1870s, two Irish brothers, veteran mercenaries in the struggles for independence, bought large swaths of land in what is now Icononzo, intending to grow coffee on their two massive estates with the very non-Colombian sounding names of Canada and Scotland. Some of the migrant coffee pickers at the Canada Estate approached one of the brothers to ask if they could build houses on the land. He agreed and built the beginning of what is now Icononzo. So, coffee, and the welfare of coffee workers, is the very reason Icononzo exists as a town in the first place. In fact, one of it’s nicknames is “the Picker’s Town.”

The Fighting

As with many post-colonial newborn countries, the systemic inequities of colonialism were deeply rooted in society, even post-independence. There were a few “haves,” and a whole of lot of “have nots.” The Catholic Church was powerful in society, a major landowner, and very conservative in its outlook.

Generally, their message, and the message of the ruling elites to the “have nots,” was to seek perfection in the next life. But not everyone wanted to wait that long. The desire for social justice, particularly as it relates to land use and reform, has been at the root of much of the fighting since the beginning. And there has been a lot of fighting.

There was the Banana Massacre of 1928, when workers at the United Food Company (now Chiquita Banana) went on strike to protest inhumane working conditions. At the behest of the U.S.-owned company, the Colombian military killed as many as 3,000 protesters, including women and children (although that number is much in dispute). That event inspired future revolutionaries. And so the wheel turns.

Then came La Violencia in the late 40s and 50s. Ostensibly a political fight between the Liberals and the Conservatives, land reform and the economic rights of the poor were at its heart. In the rural areas, where there were Liberal governments, they convinced like-minded small land holders to seize the land of their conservative neighbors, often larger landholders, and vice versa. Neighbor on neighbor violence flourished and tore apart communities.

It was so brutal during La Violenca that it is estimated that 1 in every 50 Colombians died, and millions more were displaced. And, sadly, as the violence exploded, the level of brutality also escalated in unfathomable ways. A particular way of killing began to take hold: ritualized executions, maiming, and dismemberments that were so gruesome in their methodology they garnered their own terrifying nicknames.

La Violencia subsided in 1958 with a political solution – a power sharing government. But the underlying causes of the violence weren’t addressed. And many of the children born during La Violenca would grow up to become members of the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), perhaps the largest of the insurgent groups, many of whose former members are now growing coffee in Icononzo, right next door to many families who were victims.

The FARC and the Peace Treaty

The internal armed conflict that rocked Colombian Society through the 80s, 90s, and 2000s picked up where La Violencia left off. Except there were more players: right-wing paramilitary groups, the army, and several Marxist-inspired “guerilla” organizations, the largest of which was the FARC. Not to mention a bourgeoning narcotics industry, in which all sides participated to help fund the violence.

And, of course, wherever ideological warfare turned “hot” during the cold war, the major world powers with a vested interest in the outcome were always there, too. The U.S., Russia, Cuba, etc, all with their “advisors,” funneling guns and ammunition into the churning vortex of violence.

For decades, Colombian society was ripped apart by this multi-faceted conflict that was a gordian knot of rival agendas, competing ideologies, vendettas, and a generation of combatants that had only known violence. There is not a person that we have met in any of our travels in Colombia that wasn’t touched in some way by fighting. Peace seemed impossible.

Until it wasn’t.

A process that began in 2010 culminated in the signing of a peace treaty in 2016. The FARC agreed to disarm in return for political participation, land reform, a mechanism for justice for victims, and pathway to reintegration into society. The UN and other international NGOs descended on Colombia to help implement and manage the peace. And just like that, the war was over.

Or, mostly over. There are still pockets of dissidents operating in various communities in Colombia. And political violence continues, as the recent murder of a presidential candidate shows. But mostly, the peace is holding.

How it Played Out in Icononzo

So, how do you reintegrate thousands of FARC combatants into society? The plan called for transitory rural settlement normalization zones to be set up in communities around the country, including one in Icononzo.

In these zones, former combatants would be housed and given intense education on basic survival skills in civil society. Things like how to open a bank account, and how to buy groceries, and how to find a place to live.

They would also have access to vocational training and could choose what they wanted to do for a profession. They received a stipend from the government during the transition phase, and then a cash payout that would allow them to invest in the land or equipment they would need to follow their dream.The success rate of these zones is, by many accounts, mixed.

But the one in Icononzo thrived. That might have something to do with the fact that it was the closest one to Bogata, the capital. The once sleepy town of Icononzo became the central hub for the offices of the UN and all the other interested NGOs. Restaurants, gyms, and traffic jams sprouted up, seemingly overnight. And although the UN and NGOs are long gone, the bustle in Icononzo continues.

And that is where we pulled up, in our vans full of OBIIS and Caravela team members, for our second visit in November of 2025.

Camilo Cupitre

Meeting Camilo Cupitre

He is the man of the hour. The reason we’re here. Every great story we’ve encountered in coffee has, at its center, a person who sees the world a little differently. In Icononzo, that’s Camilo.

He was born in Icononzo, back when it was a sleepy little town. He got a great education and set off on an international career in business. He lived for a while in Denmark where, despite the fact that he was born in coffee country, he had his first real coffee experience working as a barista while pursuing his education. He fell in love with everything about specialty coffee. The art of it, the finely honed techniques required to honor the potential of the coffee bean. And then he moved to Malaysia for a job in finance.

One day, he stumbled across a Juan Valdez Coffee Shop franchise getting ready to open in a shopping mall. And, excited to see something from his homeland, he offered to help. He became great friends with the operators, chipping in on weekends and after work just to be a part of it.

The year was 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic was just starting to rear its ugly head, and Camilo and his beautiful wife, Anna, could see what was coming. If there was going to be a lockdown, they didn’t want to be in Malaysia. So, they packed up and moved back to Colombia, back to the Camilo’s hometown of Icononzo.

It was four years into the peace process. The UN and the NGO presence meant that there was a large expat community in town. That was a definite plus for Camilo’s Polish-born wife, who might have been a little leery of giving up her big city international expat adventure for life in a small town in rural Colombia.

And yet, there was no real coffee shop. Camilo saw an opportunity.

Camilo and his business partner in Pomerania Coffee, Miguel.

Pomerania Coffee

There is something ironic about Incononzo. Its very existence as a community has been tied to coffee since the 1870s. And yet, almost nobody in the industry has ever paid any attention to the coffee that is produced there.

The Specialty Coffee movement of the 90s and 2000s gave birth to a global tidal wave of coffee brands all focused on high Q-Grade scores and tasting notes. But they passed over Icononzo altogether. The coffee grown there was treated as “stock lots” by the industry, fetching low market prices, and sold as an anonymous part of low-cost commercial grade blends. Icononzo coffee was an afterthought.

Camilo believed it could be different. So, he started his company, Pomerania Coffee, to showcase the quality of locally grown coffee to the expat audience. Together with his partner Miguel, they would train locals to be baristas at their brand-new specialty coffee shop. And, he would grow his own micro lots at his newly purchased small coffee farm. That was the plan, anyway.

And because he needed more coffee to serve in his shop than he could grow on his own farm, it is how he came to connect with some of the coffee producers in the area. People like Alfredo Lombana.

Alfredo Lombana and his son, Filipe.

Esperanza y Paz (Hope and Peace)

Alfredo Lombana has deep roots in Icononzo. In fact, he knew Camilo’s parents back in the day, and Camilo’s grandfather was Alfredo’s dad’s best man at his wedding.

The coffee business is a multi-generational affair for the Lombanas. He farms land that was his father’s. His daughter, Mariana, learned the barista craft and worked at Camilo’s coffee shop. She has since opened her own place in a nearby town. And his 19-year old son, Felipe, is busily soaking up knowledge on all aspects of the coffee business, from growing, to processing, to being a barista.

By the time Camilo landed in Icononzo in 2020, the reintegration process for the former combatants was four years in. Many, though not all, had chosen coffee as their profession, and used their cash payouts from the government to buy their land.

Some had chosen the area around Icononzo because it was where they had family. Some came from different parts of the country all together, with no local ties. Some had a family background in coffee. Some had no exposure to coffee whatsoever. Yet here they all were, trying to make a life out of growing coffee.

Mariana’s Coffee Shop

They relied on each other for support. And they relied on their neighbors, many of whom were struggling to heal the deep wounds and loss created by the violence their families had endured at the hands of combatants.

Another thing to know is that 2016 to 2023 were terrible years for coffee farmers. It’s a hard business anytime, but the C-Market price during those years was routinely below the cost of production. Which meant that no matter how good of a producer you were, unless you could find a way to get a premium for your coffee, getting food on the table for your family was going to be a challenge.

Alfredo saw an opportunity. Believing that they would be stronger together, he started an Association of coffee growers that he called Esperenza y Paz, Hope and Peace. Their first commercial harvest was in 2019, a year that the C-Market price for coffee dipped below $1.00 per pound. And that experience **almost** made them all want to quit coffee altogether. But they persevered.

Finding Camilo

They started working with Camilo in 2021. He bought small lots of their coffee for his own coffee shop. But he quickly came understand what they were up to as an Association. And he saw the dedication to each other and to the peace process.

They needed so many things if they were going to succeed. Better agronomy, which meant technical training. Better processing techniques and access to mechanical driers. And most of all, better prices for their coffee.

Continuing to sell the bulk of their coffee as they had always sold it, wet (meaning not dried to 9-11% humidity) through the Colombian Coffee Federation (the FNC) wasn’t an option if they were ever going to get a premium price. The needed export markets. They needed Camilo’s help.

And that’s how the vision for Pomerania Coffee morphed from a simple coffee shop to a green bean buying and exporting company.

Pomerania’s drying beds above Camilo’s coffee shop

The Opportunity with Caravela

By the time we landed in Icononzo, Camilo was working with a whole range of small producers, who had come from all sides of the conflict. He and his partner Miguel are functionally a two-man show.

They are running their coffee shop and their farm. But mostly, they are a buying station for the small producers he has come to know. He is helping them with all aspects of preparing their coffee for export, from drying to quality control to finding a good dry mill. And the trust that those producers have for Camilo is palpable.

He has had some success in exporting their coffee. He has regular clients in Poland and the United Kingdom, among others. And he sold some coffee to Caravela, although they didn’t have a presence in Incononzo yet.

But the demands on his time, his finances, his cash flow, and his credit are large. I’ve said it before, but the coffee business is a tough one to be in, and the strain was starting to show. Camilo and Anna had welcomed their first child into the world. And the demands of the work he is doing for these small producers means that his time at home with his family is limited. Not an easy place to be for a new dad.

Of course, OBIIS buying coffee from the community would be a great opportunity for everyone concerned. But it’s bigger than that. If we strike a partnership in Icononzo, it will be in part with Caravela as the exporter. Which means that they will come in to partner with Camilo, bringing with them many of their resources.

That kind of assistance could ease the load on Pomerania: access to technical experts, and agronomy technicians, access to capital and financing, and potential access to other markets. There’s a lot on the line.

Our First Day in Icononzo

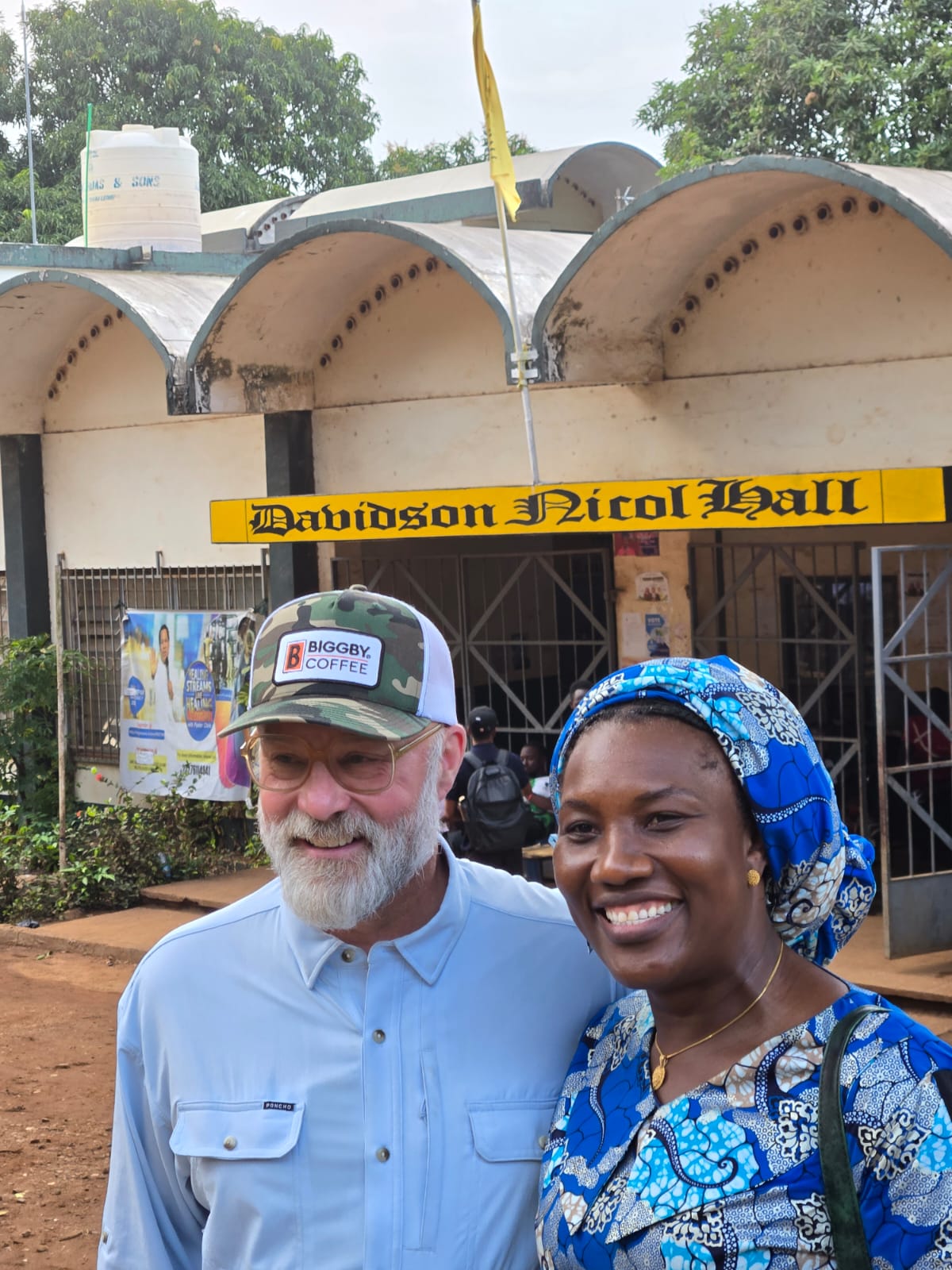

We hit the ground running after our four drive from Bogota through the Andes Mountains. The OBIIS team included me and Bob; Carlos Ferrey, part of our Farm-Direct partnership with El Recreo in Nicaragua; Matt Corbeil, an Area Representative and Franchisee for BIGGBY COFFEE; and, Nathan Havey, our long-time friend and cinematographer. With Caravela was Pedro Manga and Juan Estaban Garcia.

One of our first stops was lunch for a selected group of small producers, including Rosalba Romero Quevedo. She and her family have been farming their land for 8 years. They started with two and half hectares, but have slowly grown the farm to eight hectares, which is almost 20 acres. She was telling me that when they started, her husband did day labor to feed the family while she and her daughter cleared the weeds and prepared soil.

She is very proud of their 16,000 coffee trees and the life that is providing for her family. Her daughter still lives with them but is now involved in social work through an organization focused on improving the lives of women in the region. And her son is still studying, with hopes for a professional career in the city. Her biggest dream is that they will be able to build a proper house for her and her husband on the farm so that they can retire there.

In the beginning, she sold some of her coffee to Alfredo and Esperanza y Paz. And through him, she met Camilo. She has been selling her coffee to Camilo for three years now, and she told me that it has made all of the difference. Not only does he pay a premium for her coffee, but he offers classes that help her to be a better farmer.

Rosalba Romero Quevedo

I can’t tell you which side of the conflict she and her husband were on during the Civil War, because I don’t know. It could easily go either way. But I can tell you that it doesn’t matter. At least, it doesn’t matter today. She and her family have committed everything they have to their dreams for the future, for themselves, for their family, and for their neighbors. They are all in on peace, and on coffee, and on each other.

Leaders on the Ground

We also met Juan Cortez, a dynamo of a man, brimming with energy. He has three hectares of coffee, and his own wet mill and drier. He is also a new dad, father of twin girls we had a chance to meet in the following days. He is a lynchpin in this community of coffee producers, with big entrepreneurial dreams for himself and his neighbors. He has developed his own brand of roasted coffee which he sells to local coffee shops. And he is passionate about coffee as a way to bring the community together and to improve their economic prospects.

Juan Cortez with his daughter

Cortez, as Camilo calls him, is a true leader in Icononzo. As is his good friend, Alfredo. They were both with us through all of our stops on our journey.

The thing that was clear to us after that first lunch is how committed everyone one was to coffee, to each other, and to Camilo.

Chivas: Not the whiskey, the truck

In the afternoon, our OBIIS team loaded up into the local form of transportation: a Chiva. These brightly decorated open sided trucks are the basis of how you get around in coffee country in Colombia. They hold an unreasonably large number of people and goods, with all manner of products strapped to the roof, people hanging off the back, and all of us pressed in tight in the long rows.

Riding the Chiva

Camilo wanted us to understand the path that coffee takes in these mountains. When it comes in during harvest, it comes in on a Chiva. And it comes in on some pretty treacherous roads.

So, we started the journey up to the small town where Esperanza y Paz was planning a community meeting. We, and our colleagues from Caravela, were to be the star attraction. The ride was comically bumpy and slow, with stops every few miles for people and goods to get off and on. It’s the kind of ride that rearranges the placement of your kidneys, if you know what I mean. It’s hard on the spine. But it’s a way of life for coffee, and coffee producers in the mountains.

As we pulled into the meeting spot, we were treated to a remarkable sight: a beautiful and very vibrant double rainbow right above our heads. I don’t really believe in omens, but that sure did seem like a good sign.

The Meeting

Alfredo and Camilo were expecting maybe 10 to15 of the members of Esperanza y Paz to make the trek to the community center where the meeting was being held. But in the end, I think all 36 members were there, along with a few neighbors and other interested coffee farmers. We all crowded around in a large circle.

Bob and I have been to many, many meetings just like this. And usually, it’s us, the potential buyers, that they are there to see and to meet. But this time, it was all about Caravela.

As we went around the circle doing introductions, every single person asked for one thing: more knowledge. The only place I’ve ever seen that hungry for technical assistance was Sierra Leone. It was rather remarkable. And it was Caravela that they were talking to.

As it happens, Caravela is well positioned to help them with that. When they embed in a community, they send in their PECA (coffee producer education program) teams, which are agricultural engineers, to work with every single farmer in the program. They have a very sophisticated data gathering capability which helps inform decisions farmers make about their land with science specific to their needs. And they are transparent about the gate price they are paying the farmers for their parchment coffee.

The only hitch is they won’t embed in a community until they have a for-sure buyer to sell all of that coffee to. That’s where OBIIS comes in. For Camilo and the coffee producers we were meeting, it means that it’s a package deal. They don’t get Caravela to embed with all of their services and support unless OBIIS can find a pathway to buying the coffee.

This was our second visit. We have always been clear that it takes at least three visits before we can really begin to seal a partnership deal.

The stakes for everybody were high, and we felt it.

Yesid, center.

Meeting Yesid and Jasmine

The next day, we spent some time on the beautiful veranda of Yesid and his wife Jasmine’s farmhouse. Yesid’s father purchased the land for the farm 40 years ago. At one time, they grew mostly sugar cane. But over the decades, they have converted almost all of it to coffee.

I was particularly struck by Jasmine. Despite the struggle and all the challenges that they have endured in their decades’ long experience in coffee, she is fiercely proud of the work they do, and the impact that they have in their community. She told us that everything they do, they do with love and intentionality, from growing their coffee to taking care of their workers and their workers’ families.

Jasmine

It was Jasmine who called out how remarkable it was to have all the players in the value chain of coffee together on her veranda. From themselves, the growers, to Camillo, to Caravela. And, most astonishingly to her, the retailer. She pointed to Matt Crobeil and said how meaningful it was to meet the person that actually puts the cups of coffee into customers’ hands. Her only regret is that the pickers were not represented, because their role was perhaps the most difficult and precarious in the whole chain.

She told us that her dream is to be able to do more for the coffee pickers and their families. But the price that they can get for their coffee through the FNC is barely enough to keep them going. She was hopeful that a partnership between us, Caravela, and the community in Icononzo would mean better support, more technical assistance, and better prices. And most importantly, a better future for everyone.

She is a powerful voice, and you could have heard a pin drop while she was talking. But she wasn’t the last powerful woman we were going to meet that day.

Adriana and the Cup of Excellence

Next up was a very special lunch that may well haunt my dreams for the rest of my life. I’ve never seen a plate of food quite like it. A pile of rice with a perfectly cooked fresh farm egg on top, surrounded by all kinds of meats and sausages, black beans and fried plantains. And accompanied, of course, by a bowl of the most delicious chicken soup you can imagine. Our hostess was Adriana Diaz Castillo, and we were there to hear her story.

The most amazing lunch

Adriana and her husband had been working in Bogota as young professionals in careers that were bringing them less and less satisfaction with every passing year. They decided to chuck it all in, buy some land in Incononzo, and start an organic chicken farm.

Their timing was exceptional. Soon after they got the chicken farm up and running, the pandemic hit. And as fate would have it, the primary egg supplier for that region was based in Bogota. When the lockdown began, egg shipments from the capital stopped. And Adriana’s farm was there to pick up the marketplace.

Almost as an afterthought, she also planted one hectare of Geisha, a highly-prized, difficult to grow variety of coffee that is renowned for its refined flavor. Neither she nor her husband had any experience in coffee. And she found growing Geisha to be very fussy and not particularly rewarding. In fact, she was thinking about ripping it all out,

But then, almost by accident, Camilo heard about Adriana and her Geisha, and he came to her farm to check it out. He was impressed and encouraged by what he tasted. He convinced her to not only keep growing her Geisha, but to enter it into the national competition, famous in coffee country, called Cup of Excellence.

Adriana, center

They spent months together perfecting the processing to create the most promising sample. And they hoped that she would get a good score, and maybe even place in the top 20 in Colombia.

Instead, she won it. The whole thing. Her coffee that she had been struggling to sell was suddenly worth hundreds of dollars a pound to an international audience. And Icononzo, long overlooked by the entire coffee industry, was officially on the map for quality coffee.

The Deluge, the Wet Mill, and Goodbyes

She is a star in her community, and Cortez and Alfredo, who were with us at the lunch, treat her like a favorite daughter. You can feel the pride the entire community has in her accomplishment. She beams with it. And she, in turn, does everything she can to support the coffee community of Icononzo.

We were a case in point. There is literally no chance that we will buy her coffee. BIGGBY COFFEE isn’t the kind of coffee shop where you would expect to find a $50 pour-over. Yet, she was hosting us to a most sumptuous, generous lunch, and showering us with all her attention and her warmth.

Adriana’s Wet Mill

Later that evening, after waiting out what felt like a Noah and the Ark level deluge of rain, we headed over to her farm to see her wet mill. Honestly, I’ve never seen a wet mill like it. What is usually a quasi-messy, slightly smelly monument to functionality, where the coffee cherry gets depulped and washed, felt like a spa. Everything was paneled in wood her husband had carved by hand. There were rocking chairs, and a veritable jungle of lush plants and flowers decorating the entire space.

Our merry group was lively with conversation. We were coming to the close of our time in Icononzo, but the energy had been exceptional. We were all buzzing with the heady potential we could feel in this community.

This place and the people growing coffee here felt a bit like a miracle. And if this is what it can look like when the ink dries on a peace accord, then maybe there is hope for the seemingly intractable conflicts that are engulfing so much of the world today.

There is still a long way to go before we could officially cement a new Partnership. This was only our second visit, after all. And everybody knows that it takes us at least three times to really make the leap.

As our group was milling about, laughing and talking, Cortez was by himself in one of Adriana’s rocking chairs, seemingly deep in thought. He said something out loud. Bob thought it was to him, so we scrambled to find a translator. It was a funny moment, because Cortez didn’t realize he had said anything, and so he thought Bob was trying to start a new conversation.

Turns out that what he said was “Come Back.”