In 2022, I was standing in front of an audience of about 1,000 people at the BIGGBY NATION SUMMIT when I made a very bold promise. I said that we could guarantee that there would be no child labor involved in the production of any OBIIS certified Farm-Direct coffee.

It felt powerful to say those words out loud. It felt so good, in fact, that I said it again on that same stage in 2023. And I know the people that were there to listen to Bob and me give our OBIIS update really wanted to hear it.

There’s only one problem. I didn’t know what I was talking about.

Don’t get me wrong, I would like very much for that to be true. But it’s not how the world works in most of the countries where coffee is produced. I just didn’t know it yet.

What We Knew in 2022

The first time I made that grand pronouncement on stage, we had two Farm-Direct partnerships under our belt. One was with Living Hope, the orphanage in Zambia that started a coffee farm to make itself more sustainable. No child labor there. Check.

The second was with El Recreo in Jinotega, Nicaragua. They are a mid-sized farm of 180 acres, started by a highly educated, very socially minded family of (relative) means. We’ve told the story of Leana Ferrey witnessing her new farm’s first harvest in 1972, and the shock she felt when she saw so many coffee pickers arrive with their children, expecting them to work.

That wasn’t going to happen on her watch. So, she figured out how to build and run a school on the farm and insisted that no children work in the fields.

The Ferrey family’s legacy of providing education for the workers and the children in their community is truly inspiring. It’s one of the many reasons we fell in love with that farm and that family. No child labor there. Check.

The worker’s children at the school the Ferrey family built on the El Recreo Coffee Estate in Jinotega, Nicaragua.

Size Matters

It’s entirely possible that had we continued to focus solely on developing partnerships with mid-sized farms, we would be able to keep that promise. Mid-sized farms tend to have many more resources, connections, and the ability to drive change.

But more than 60% of the coffee that is produced in the world is grown by farmers with less than 12 acres. Even that, as a statistic, is deceptive. Because most of those 60% of producers are farming many fewer than 12 acres. In the places we’ve been, we more commonly see people farming one or two acres, maybe less than that. We call them micro-producers.

These micro-producers have little to no resources. Most live many rungs below what would be considered the poverty line, even by their own country’s standards. They are people for whom access to adequate food and clean water can be a daily struggle.

Meeting with some of the micro-producers that make up the Kogimuwaka Cooperative in the Huye District of Rwanda. These micro-producers typically own so little land that they don’t measure their farm in land size, but rather in the number of trees in cultivation. Most support their families on fewer than 400 trees, which would be less than an acre.If we’re going to change the coffee industry, and have an impact in the poorest communities, we have to reach those farmers. And the conditions and challenges in their communities are complicated. Particularly when it comes to child labor.

The Epiphany

In December of 2023, the OBIIS team went to Mexico to visit our partners Maria Esther Saut and Pascual Castillo at Finca La Fortaleza. They are also a mid-sized farm, dedicated to working with the smallest producers in the very poor region of Chiapas.

Through our Farm-Direct partnership, we buy around 200,000 pounds of coffee from them each year. 60% of it comes from Finca La Fortaleza. 40% comes from four small carefully chosen producers that they work with.

Carefully chosen because their approach to farming aligns with our values around treating people right, practicing sustainable agriculture, and investing in their communities. Because of their size, these producers would never have hit our radar without the help of Maria Esther and Pascual Castillo.

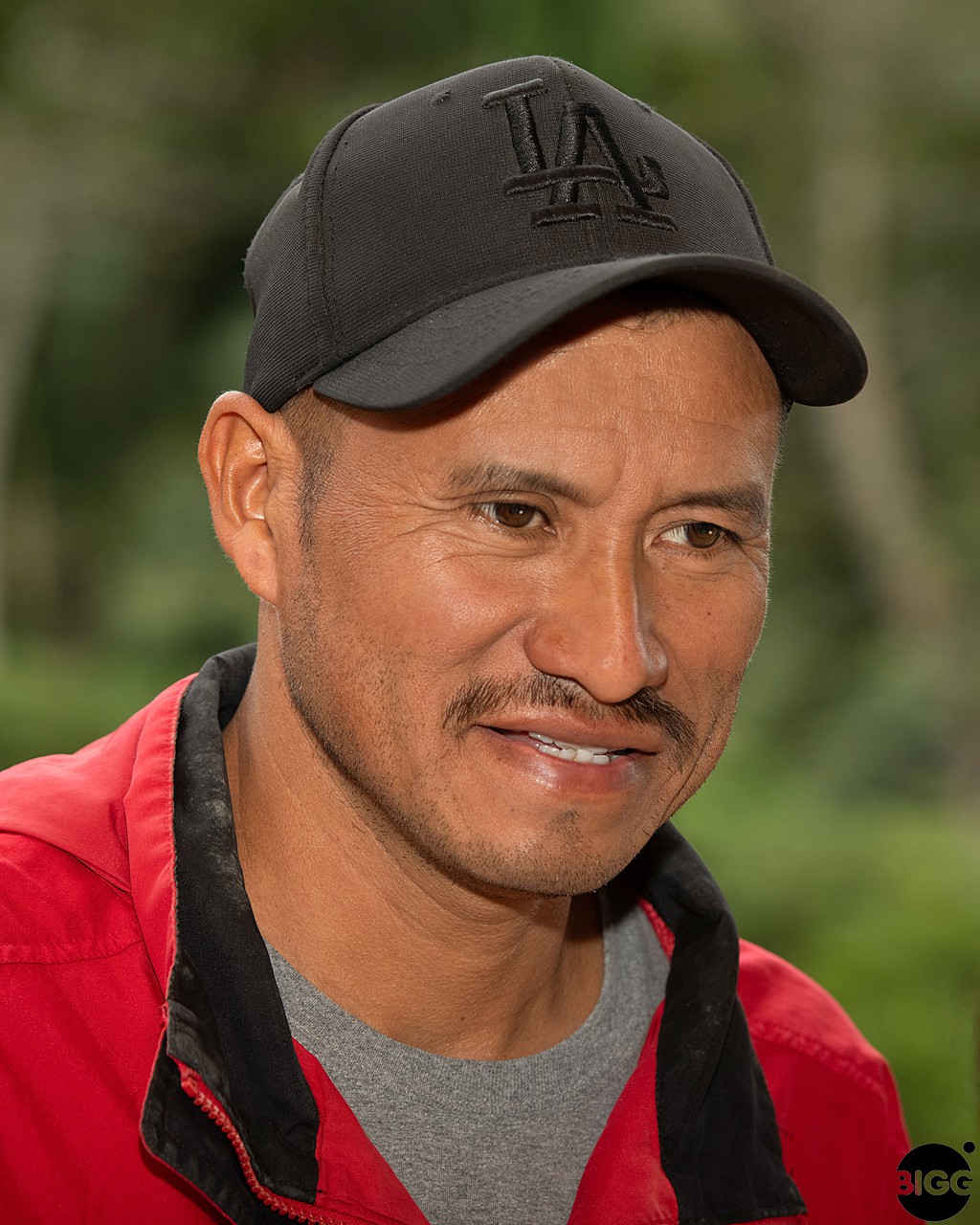

Maria Esther and Pascual Castillo.

One of the great joys for us on that kind of trip is walking the fields with the small producers.

It’s powerful to see the impact our partnership has had over the last year, as these farmers move from survival mode to dreaming bigger.

We were walking with Salomon Demeza and his family on his beautiful 10-acre coffee farm. He was justifiably proud of his new plantings, and all the work he had done over the past year to bring more of his land into production. But he saved his proudest moment for last.

Salomon Demeza with one of his new seedlings.

The Neighbors

He has been able to hire help. And he is very proud of the fact that, for the first time, he can now create direct economic opportunities for others that are struggling in his community.

He has a neighbor with a very small coffee farm that is barely breaking even. That neighbor supports his pregnant wife, four children, and father-in-law on less than two acres of coffee.

Salomon was able to hire the family to help him pick this year’s crop, giving them an entirely new income stream. He pays 3.5 pesos per kilo of coffee cherries, which is above the regional average. On a good day, the family might pick 100 kilos, which means that they’d make about $20.00 per day.

This has been an absolute boon of good fortune for his neighbor. And has done much to help stabilize their family’s day-to-day living.

The neighbors wife, working in Salomon’s field. On the day we were there, the neighbor was at home tending to his own coffee farm. But we met his neighbor’s wife, the father-in-law, and his four children, the youngest of whom couldn’t have been much older than three. They were all picking Salomon’s coffee in the field.

School

It was a shock to all of us, but particularly me. In my head, I could hear myself on the BNS stage in 2022, almost trembling with my over-confidence, shouting out to the world “no child labor!” And yet, here I was.

I asked Salomon why those kids weren’t in school. The underlying challenges may be complicated, but the answer to my question was simple. The family can’t afford it, and there is no nearby school to go to.

It is a two-hour walk, each way, to the nearest school. And it costs about 100 pesos ($5.86) per child per day, in school fees, uniforms, and supplies. That is simply out of the question for Salomon’s neighbor.

In fact, it’s out of the question for most of Salomon’s neighbors. When the choice is sending a child to school or providing shelter, food, and water for your family, what are you supposed to do?

Two of the neighbor’s children carrying the coffee that the family had picked.Now, imagine those same parameters in small community after small community, all throughout coffee country. It is a fact of life for the smallest micro-producers, eking out a living on an acre or two, in the very remote and under resourced communities where coffee grows.

Many of the kids are not in school. Either they don’t have one to go to, or they can’t afford it, or both. So, they’re working with their parents.

If we are going to change the fortunes of those kinds of small producers around the world by buying their coffee the OBIIS way, I can’t say that there won’t be child labor involved. In fact, I can almost guarantee that sometimes, there will.

So, what do we do now?

The Conversation

As you might imagine, the conversation among our OBIIS team was pretty lively that night. There was a lot of debate and back and forth about what child labor really means, and what our response should be.

Because we’ve worked primarily with mid-sized farms up to this point, it’s as if we’ve been flying in an airplane at 2,000 feet, almost ready to land, but not quite. We were close enough to see the poverty in the communities we visit, but we hadn’t fully understood all the ways it plays out in the lives of the people.

On Salomon’s farm, we got the view from ground-level. It was shocking and disheartening to be confronted with the reality of the world we’re in.

One option is to tell Salomon that from now on, he can’t hire anyone that might bring their children to the fields with them. But that family would almost certainly lose their access to the new income stream that Salomon made possible, and the improved quality of life it brings them. After all, the mother wouldn’t want to leave her kids at home alone. And even if she did, the kids still wouldn’t be in school.

Also, we never tell producers what to do.

We could keep our “no child labor” promise, throw in the towel, and stop working with small producers all together. In a lot of ways, that would make us look great. Our marketing would be “holier than thou” powerful in its absolutism. Thanks to our “boots on the ground” methodology and the values alignment we have with our mid-sized partners, we could keep the promise real.

But it wouldn’t change anything. Not in Salomon’s community, or in countless others all over the world.

Worse, we would be completely abandoning more than 60% of coffee producers and their families, because we couldn’t be sure about child labor. I’ve met so many of those families now. And I can tell you that they’re the ones that really need us.

Assumptions

We all make assumptions about what’s possible based on our own experiences. One of my assumptions (and I firmly believe this) is that access to education is one of the most powerful ways to lift people out of poverty. A good education gives people choices. And having choices is the gateway to changing one’s personal circumstances.

Salomon Demeza agrees. His kids go to school, and they pay the 100 pesos per child per day to send them, as well as arrange for transportation through his brother’s taxi service. But his economic fortunes with a 10-acre coffee farm and a partnership with OBIIS are completely different than his neighbor’s.

Salomon with his wife Viviana and their youngest son Allan Benjamin. Their older two children were in school on the day we visited.As it happens, Salomon was interviewed by our cinematography crew in the days before we walked his farm. On camera, he told us his big dream is to build a school in his community. It’s not a thing he can do on his own. But he is determined to muster the resources through his own ingenuity, his community, his connection to Maria Esther and Pascual, and through the government.

It may take a few years to come to fruition. But he is determined. He wants a better life for the children in his community, too.

Price

We never tell the producer, large or small, what they should do. We look for producers, large or small, that treat their people right, farm in a way that is regenerative rather than extractive, and invest in their communities.

Then, we pay them a price for their coffee that is based on the economics of their farm. The C-Contract, which governs the global market price of coffee, is completely irrelevant to us. We’ve written a lot about why we do it that way, and you can read more here.

Once we forge a partnership, it is our intention that it be perpetual so that the producer has the kind of surety that allows them to make investments and plan for the future.

It has been our contention that if you pay the producer in the right way, they will make the right investments, based on the needs of their farm, their family, and their community.

And here is Salomon, finally out of survival mode. Now that he’s being paid the right way for his coffee, one of the first things he wants to do is figure out how to get a school built.

I’m not saying that OBIIS is the cure for lack of access to education in coffee country. And I’m not saying that everywhere there is child labor, the first thing a small producer will do with economic stability is to build a school in their community. But it’s encouraging to know that’s where Salomon has landed.

That still doesn’t answer the question about our approach to child labor.

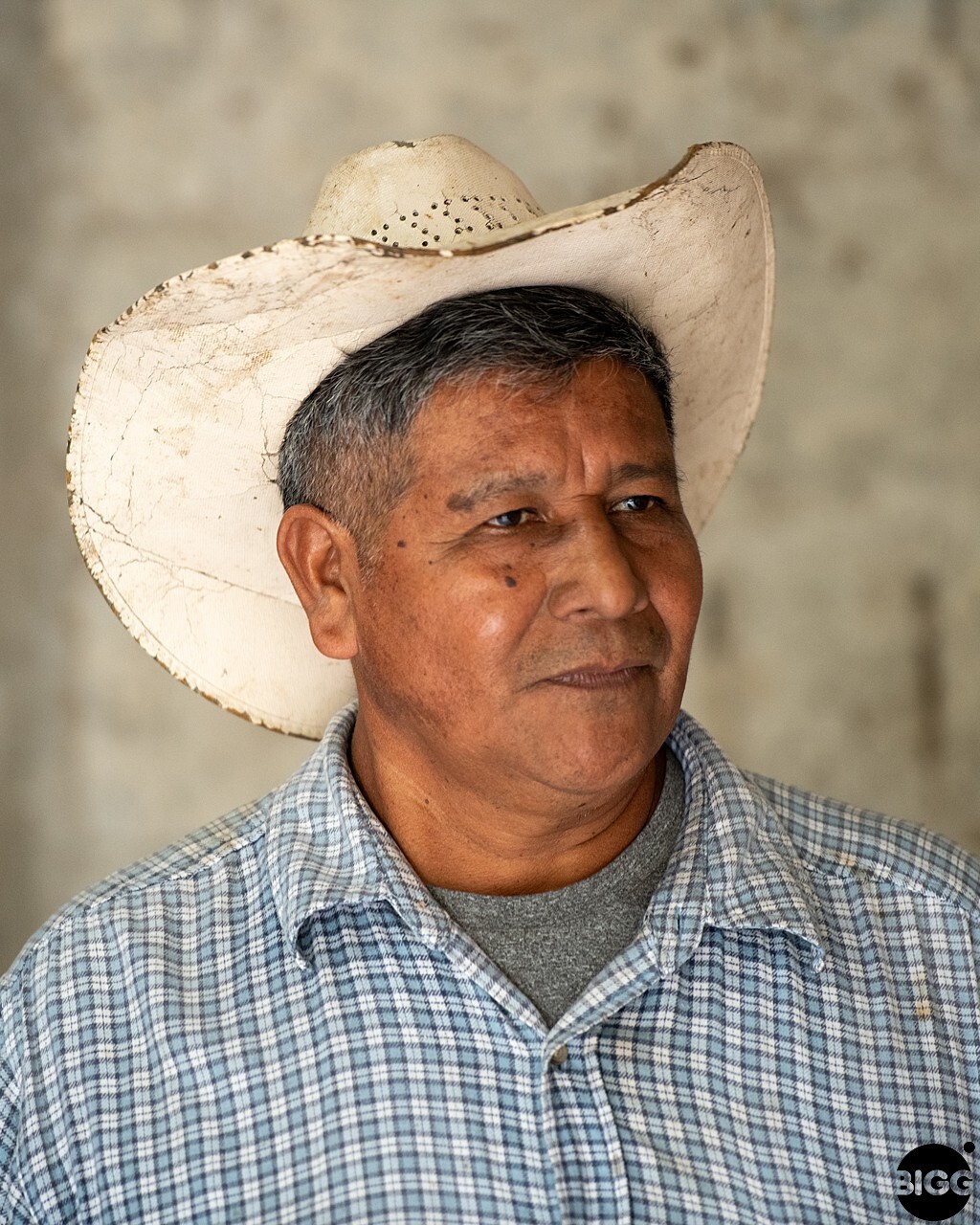

Ivan Vasquez, bottom left, was an enthusiastic tour guide for Kim Zahnow, our photographer (upper left), and Alysha Burney (upper right) and Lorna Parra from our cinematography crew.

A Different Perspective

At the table with us on that night in Chiapas for our big OBIIS conversation was Ivan Vazquez. He is the nephew of Martha Vazquez, another one of our four small producers in partnership with Finca La Fortaleza.

In addition to being a micro producer himself with about an acre of coffee just down the street from his aunt’s, he owns his own construction company, has a degree in journalism, moonlights with La Fortaleza on various projects, and speaks excellent English.

He listened, patiently, to our conversation for a long, long time. Until I think he felt he’d finally had enough of our handwringing.

As he explained it to us, we were missing the point. In the community he grew up in, the town of Esperanza Morrison in the Tumbala region of Chiapas, education wasn’t the most important thing parents hoped to impart to their children. Work ethic was.

What Makes You Free

Ivan said that in his community, they understood from generations-long experience that what makes you free is the ability and the willingness to work hard. So good parents teach their children from the youngest, most tender of ages, that work – hard work—is what will give you a future.

His question to us is why would we be so distraught at the idea of Salomon’s neighbor’s kids learning how to work? In the world that he came from, being taught how to be an efficient coffee picker from a young age would mean that you could always find work. And if you can find work, you can live.

I heard him. I really did.

But yet… he’s a coffee farmer, who owns a construction company, moonlights with La Fortaleza, and speaks excellent English. And has a degree in Journalism from the University.

His grandmother made sure he got his education by paying his fees and walking him to school every day in that poor, under resourced community. He has choices. He’s made a very interesting, inventive, creative, successful life for himself based on the things he loves. One of those things is his community, and he invests in it every way he can.

As it happens, I think he and I are both right. Hard work can earn you a living. And a good education can give you choices about what kind of living that is. If you have both, you can be free.

Kids at the newly opened bilingual school at Finca Terrerito in Corquin, Honduras. The school is a joint project between our Farm-Direct partners Al and Leticia Lopez and the Matiak Foundation. Before this school opened in February, 2023, the students pictured here didn’t have a school to go to that they could afford. This school is free to the workers children at Finca T and the kids from the nearby village. It is a game-changer.

So, What Do We Do?

This is a really hard issue for me, personally, and I have struggled mightily with what to do.

I feel more comfortable in a world where I can take stances that are absolute and black and white. But if this work that we’re doing with OBIIS is just about me feeling more comfortable, then there’s not a lot of point to it.

If we’re going to create positive change in the coffee industry, then we are going to have to find a way to work with some of the smallest producers, in some of the poorest regions around the world. To do that, we have to meet them where they are, not where we wish they were.

If we’re going to work with the kind of small producer that needs us most, then we’re going to have face the fact that on some of those small farms, there will be young hands in the fields. They don’t have any real choice. And we’re not going to punish them for that.

It’s perhaps worth noting that child labor is both hard to define and not a monolith. There’s a scale that ranges from kids working on their parent’s farm on the weekends and after school (is that child labor?) all the way to kids sold into slavery, working in very dangerous conditions for long hours, with no one to attend to their health, safety, and wellbeing.

If you want to know more about that, I suggest you watch an excellent episode of Last Week Tonight with John Oliver. He took a deep dive into the cocoa trade in Africa, which has a lot of similarities to the coffee industry. It’s worth watching.

I think we can be as absolute as we’d like on the latter. There is no child slave labor on any of the farms we’re working with. I can, in all good conscience, guarantee that. Keep in mind that to become one of our partners, we’ve already established that you are a person who treats their people right.

But life in those communities isn’t going to change substantially until there is economic opportunity there, too. The system as it exists now, is rigged to keep them in poverty. The C-Contract, sometimes nefarious brokers and middle-men, and the challenges that climate change pose are the real threat.

OBIIS isn’t a panacea to the challenges they face. But having a legitimate shot at economic stability can create change. We want to work towards a world in coffee in which all children have the opportunity to get an education. And we’re going to do everything we can to create the conditions where communities can make that change for themselves.

That’s a promise I can be absolute about.